Independent Watchmakers Reinventing the Future

By Kwan Ann Tan

Discussing the future in relation to mechanical watchmaking is difficult and rather paradoxical. Fundamentally, watches have not changed very much since the days of Breguet and, arguably, every watchmaker creates their pieces with longevity in mind. From perpetual calendars that will be accurate for the next few centuries, to some of the most famous advertisements for watches emphasising their hereditary nature, it’s a small way in which we can control our immediate present, while also anticipating what is yet to come.

In terms of the future of watchmaking, the independent sphere is undoubtedly where some of the most interesting research is appearing. From Roger W. Smith’s applications of nanotechnology to his movements and the unique dial configurations found on Ressence’s watches, to the playful and unconventional spirit found within pieces made by Konstantin Chaykin or MB&F, a spirit of creativity and innovation reigns within these watchmakers, unfettered by stakeholders or marketing campaigns.

How We Make Watches

Independent watchmakers often take risks in the way watches are made – whether it be through innovative methods of construction or in the materials used. For others, discovering new ways to create watches that improves traditional methods can be even more experimental.

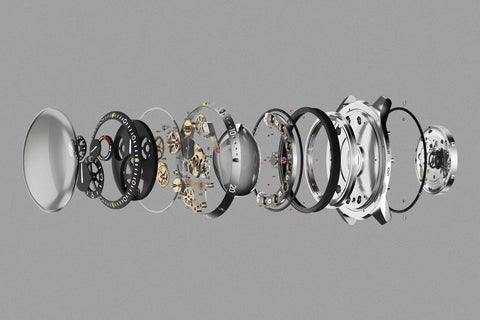

The traditional making on an unconventional watch, the Konstantin Chaykin Mars Conqueror Mark I, courtesy of Konstantin Chaykin.

While mechanical watchmaking has always been slightly suspicious of newer materials, preferring to stick to tried-and-tested metals such as brass and gold, pushing the limits of the modern world remains appealing – and will inevitably influence watchmaking’s development.

Nanotech-Lubricants

Out of all the technologies discussed within this article, this is potentially one of the more revolutionary, and has the best chance of being widely adopted when the technology has been fully developed. Roger W. Smith explains: “The idea behind the nanotechnology is hopefully to be able to remove lubrication from the watch. Now, whether that’s in part or in its entirety, we just don’t know yet.”

The problem of lubrication is one that has plagued the watchmaking world for as long as watches have existed. When animal fats were used, the inner workings of the watch would be stopped by the build-up of dried oil. More recently, synthetic oils are used. These tend to evaporate, creating even more friction and causing greater wear to the parts. By removing the need for lubrication entirely, the watch could, theoretically, run forever.

When asked about the status of the project, Smith shares that, despite the work being unavoidably slowed by Covid, they have already begun testing several components within the watches. “It seems to be working very well at the moment,” he says. “We know it’s not a perfect science, and there is a lot to work on, particularly with the scaling of components and trying to apply that process to smaller components.

“We’ve coated a barrel arm and that’s working brilliantly, with absolutely no lubrication on it at all. That’s great, but I’m very keen to see how we can develop the nanotechnology for work around the escapement area and so on. That’s where the real test for me will be.”

A Roger W. Smith Series 1 watch, and a glimpse of the escapement, where Smith hopes the technology can be applied.

However, Smith highlights that the technology is in no way a replacement for the craft that goes into watchmaking. “That’s the beauty of [this technology],” he says. “It could be applied to any existing clock or watch, so that’s the great advantage to me as a watchmaker. I get to keep my artistic integrity and still make the watches I like. After all, the coating is on the nanoscale, so dimensionally it doesn’t alter anything.”

Of course, there are potentially far-reaching implications for the industry: a reduction in servicing will also come with its own financial entanglements that will have to be reconciled, if the technology takes off. But while watches’ waterproofing will still need to be tested and maintained, a substantial amount that goes into the general service on a watch could disappear. The technology could change how watchmakers approach creating pieces, as they would be safe in the knowledge that their work would be able to live on far longer than before, affording a greater space for creativity and innovation. This is especially interesting for independents, as it might mean that less of their time will be taken up with servicing existing watches, leaving them to concentrate on their art.

Getting down to the basics of how the nanotechnology will actually work when applied to the watches, courtesy of Roger W. Smith.

When asked about what he sees for the future of the project and what it might mean for watchmaking, Smith says, “it’s difficult to know what will happen. But if we do get to a point where we’ve proven the technology, it would be wonderful if it was accepted. But that’s probably a long time away.”

3-D Printing

Some watchmakers have chosen to go down an entirely different path. Using technology to print components has been around for some time, with CNC (Computer Numerical Control) machining being able to create parts that would otherwise be too difficult to make by hand. This allows for greater freedom in terms of what is possible for a watch, as seen in the forward-looking, intriguing designs of brands such as Urwerk, who are happy to embrace the technology needed to help them create their vision.

A 3-D printed case by Holthinrichs Watches, courtesy of Monochrome Watches.

More recently, 3-D printing has also allowed watchmakers to explore new avenues within design, such as in the case of Michiel Holthinrichs, an architect-turned-watchmaker whose watches make use of 3-D printing to realise his cases. Using a combination of traditional movements and 3-D printing, Holthinrichs has been able to print cases that are later assembled and finished by hand. In instances like these, there is less of a reliance on external suppliers so there has been a marked shift to in-house production across the industry, and the benefits of it are widely known.

In 2014 and 2016 respectively, there were two attempts made to print an entire tourbillon – blown up to a significant size, rather than within the smaller scale of a watch. However, due to various technical problems and the fact that the technology is not quite there yet, the projects were abandoned. It is inevitable that technology will finally catch up and allow for more precision while printing.

The Tourbillon Mechanica Tri-Axial, released in July 2020, courtesy of Mechanistic.

When the time comes, it will be quite easy to imagine a community based around sharing blueprints and tips to put together a watch, resulting in the further flourishing of exploratory and potentially innovative new work. We are already seeing parallels of this in open-source communities which share software solutions and code. Meanwhile, shared 3-D printing knowledge is already making substantive changes in the wider community, more recently even allowing users to print objects such as medical supplies.

Silicon

In 2001, the Ulysse Nardin Freak made use of silicon inside a watch’s escapement for the first time. Hailed as the material of the future, silicon has since become more widespread within the industry, although it is perhaps not entirely as revolutionary as collectors in the 2000s might have once assumed. There are certainly benefits to the material: it does not require lubrication (another way of coming at the problem that Roger Smith is trying to solve); it is inherently anti-magnetic; and it is more resistant to changes in temperature.

Twenty years on: from the Ulysse Nardin Freak to the Zenith Defy Lab, courtesy of Sothebys and Professional Watches.

More recently, while silicon may not have changed the fundamental components of a watch, it has changed how we think about making watches. Take, for example, the Zenith Defy Lab from 2017. Here, silicon is used to make the oscillator, combining around 30 parts that make up a traditional regulating organ into a single wafer of silicon, allowing for higher speeds of vibration compared with a traditionally made mechanical watch. The silicon oscillator is a single piece that gets rid of the need for a lever altogether, reducing the possibility of errors and massively streamlining the watch’s components.

Just last year, in 2021, the Frederique Constant Slimline Monolithic Manufacture was created, building upon the principles suggested by the Defy Lab to explore the limits of a silicon oscillator. The piece departs rather significantly from traditional watchmaking, especially given the fact that the silicon oscillator is made up of only three parts, instead of the traditional 26. This means that it can oscillate at 288,000 beats per hour – a significant feat once you consider that a typical mechanical watch usually runs at about a quarter of that number.

The wafer-thin silicon oscillator that can be found within the Frederique Constant Slimline Monolithic Manufacture, courtesy of Monochrome Watches.

While silicon has been used more widely within the industry, there hasn’t been a response to the material on the same scale as say, the Quartz Crisis – but notably, according to Europa Star, that might change once the patent on the industrial production of silicon balance springs expires this year. Furthermore, there are limitations to silicon that make it less favourable, especially when it comes to potential longevity. What’s more, that handmade quality – the draw of traditional watchmaking – is missing.

One thing is almost certain for these independent watchmakers – it is extremely unlikely that there will be a cataclysmic shift in terms of the materials they use.

Despite the futuristic movement, the Frederique Constant Slimline Monolithic Manufacture is very classically styled, courtesy of Monochrome Watches.

“You could go into an auction house and buy a pocket watch that was made in the 1500s or 1600s and, with very little work, could bring it back to its working condition,” says Smith. “And that’s simply because they’ve used tried-and-tested materials.”

Similarly, Philippe Dufour has spoken publicly against the use of silicon in watches, citing the fact that while traditional watchmaking makes use of fundamental, raw metals that will still be around for years to come, the fate of silicon machines and materials are less certain.

How We Think About Time

While reading time practically rules our entire lives, we often take the process for granted. However, some watchmakers are reinventing how we both read and understand it, which could mean that in the future we will use watches – and read time – differently.

Celestial Bodies

Some makers, such as Ludwig Oechslin at Ochs Und Junior, focus on conveying a different experience of time, as seen in the brand’s Perpetual Calendar. At its most basic, a perpetual calendar watch will be able to function without correction for 100 years after it was first created. In comparison, the Ochs Und Junior Perpetual Calendar expands that to an accuracy of up to 3,000 years, a staggering difference achieved by the addition of four extra components. The number itself is not difficult to comprehend, but when you consider that our individual life spans are unlikely to graze 100 years, this promise is astounding.

The pieces that comprise the perpetual calendar, and fitted into the watch itself, courtesy of Ochs und Junior.

Additionally, the design of the piece is intriguing in itself: there is a minimalistic dial and a slightly asymmetric spiral representing the dates, emphasising the visual presentation of the changing days rather than with the sub-dials of a traditional perpetual calendar. The pared-back design also fits their ethos of creating simple timepieces.

Another way of looking at the future can be found in the work of Konstantin Chaykin – in particular, the watch Mars Conqueror Mk 3. This piece looks far into the future to a time when humans might inhabit Mars. In addition to its futuristic look, the watch itself is designed for use within space, with a bezel that is movable even when the owner is wearing a spacesuit. The second sub-dial also displays Martian local time, as a day on Mars is approximately 44 minutes longer than a day on Earth. Chaykin’s design demonstrates the potential that exists within futuristic design when it is allowed to flourish; it is truly “forward-looking” in a way that anticipates a potential future wearer’s needs.

Chaykin’s work is set against the backdrop of the modern Space Age, focusing on experimenting with cosmic complications. Both his Only Watch 2021 Martian Tourbillon and the Martian Perpetual Calendar provide us with very different ways to approach time, reading it on another scale entirely. Even if Mars does not end up becoming a second home for us, it certainly bodes well for intergalactic watchmaking of the future.

Digital Brainwaves

Ressence is another brand that is making waves in how we read time, revolutionising how we can combine modern technology and trusted traditional techniques.

Ressence watches are split into two modules: a lower half, comprising a customised self-winding ETA 2824/2 ébauche, and a display module, or ROCS (Ressence Orbital Convex System). This orbital system then allows the dials to move around a “fixed” point at the centre of the dial, much in the same way that planets move around the sun.

The ROCS display module found on Ressence watches.

Despite the initially confusing layout of the dial which goes against how we usually read time, it could be that Ressence’s displays are more intuitive to read than a standard clock face. Benoît Mintiens, the founder of Ressence, tells us that a few years ago a professor at the department of neuroscience at Harvard University contacted Ressence. He asked for permission to use their timepieces in an experiment that explored how quickly the brain can understand time as displayed through different layouts and indications, suggesting that Ressence’s dial could potentially be more efficient than a normal dial. Although they eventually found that the dial still fell short of the efficiency of regular dial, it has paved the way for more experiments in dial design, for which the company has plans in the works.

For the Type 2 Ressence, the company has also introduced the “e-Crown” – a piece of technology that can link to the wearer’s phone and allows time to be set manually or via an app. Perhaps even more crucially, the e-Crown is not solely linked to this watch model and can be used in other watches. Obviously, this does not mean that it can be directly transferred to your current favourite watch, but it does leave the door open for other watchmakers to attempt to integrate it with their own work.

Up close with the Type 2 e-Crown, courtesy of Ressence.

On the future of watchmaking, Mintiens tells us, “Functionality is key. Let’s not forget that we are in a world where most, if not all, [watchmaking] brands don’t even consider functionality. For any other product, if it’s not functional, it has no relevance. If my car isn’t starting in the morning, it’s a bad car. Well, if your watch is not comfortable on your wrist, it’s a bad watch. If the watch doesn’t fit your identity, it’s a bad watch, etc. There are so many areas you can work on to improve the functionality of your product, and really for me, that’s the future of fine watchmaking – and of any product.”

Functionality is often a secondary concern for an industry that prides itself on its craft and artistry, but there is something to be said for mechanical watchmaking proving that it can exist symbiotically with modern technology, bolstered rather than overwhelmed by it.

How We See Time

This is perhaps the most nebulous of the categories, as it is impossible to entirely predict what independent watchmaking might look like in the future. Arguably, watchmaking has responded to and taken inspiration from different design eras through the years, while sticking rather solidly to the same configurations. Here are a few that are testing those limits.

Senses Other Than Sight

An honourable mention must be given to some watches and brands that are completely bypassing traditional methods of reading the dial in favour of style or concept. They are not necessarily mutually exclusive, but some are certainly more practical than others.

In terms of accessibility, the brand Eone focuses on inclusive design and their Bradley Timepiece allows the wearer to tell the time not only visually, but physically too. It has raised hour markers and ball-bearings that travel around the watch face – perfect for visually impaired people, or for reading the time in low light conditions.

The tactile-focused dial of Eone’s Bradley Timepiece, courtesy of Eone

On the opposite end of the spectrum, we have H. Moser & Cie, known for their “Concept Series” – watches with minimalistic, nearly-impossible-to-decipher dials stripped down to just the hour and minute hands.

While it’s difficult to say if these pieces will ever be assimilated into the mainstream, they are definitely part of the future of watchmaking, raising questions of accessibility, design, and most existentially, the function of watches.

Creativity in Design

For other watchmakers, thinking about “the future” is not as important as producing a design that is innovative and goes against the grain with what a watch can be.

An UR-100 and UR-105, pieces that exemplify Urwerk’s retrofuturistic take on watchmaking, courtesy of Urwerk.

More recently within the field of independent watchmaking, we have seen exactly how inventive these pieces can be, such as in the original lines of MB&F or the futuristic work of Urwerk and Vianney Halter, with pieces like the UR-Satellite or the Resonance giving a unique twist to established mechanisms. Perhaps most curiously, many of these draw on retrofuturism, rather than any accurate insight into the future.

As Max Büsser says, “We’re not innovating because we want to change the world of watchmaking. We’re innovating because we want to change our own world. Once something has been done, there is absolutely no point in doing the same thing because it’s impossible to feel truly proud of it.”

What is perhaps most interesting is the shift and desire for something new in a world that is constantly seeking to reinvent itself. Büsser stresses this need for invention particularly in terms of design: “There are brands that typically come up with a great idea at one point and keep working on that idea for maybe the next 40 to 50 years, but a truly revolutionary brand is one with which every time they come up with an idea, they say ‘Ok, well, that’s done. Let’s do something different now.’”

Where Will We Go From Here?

The difference between independent watchmaking and bigger players in the watch industry is that for the former, the spirit of independence is what allows them to create. It makes them most likely to innovate – something which will probably not change as we move into the future.

As independent watchmakers now have to contend with an increasing demand for their pieces, they seem to have reached a sort of crossroads. Büsser tells us, half-jokingly, half-seriously: “We’re facing a lot of pressure from the market and our clients, because if someone on the waiting list sees that we’ve come up with a new product, they might go, ‘No, no – don’t create anything new. Finish making my piece first!’ So, for me, being able to continue creating is incredibly important.”

But, of course, technology in our modern world has yet to unlock its full potential – and this will continue to influence watchmaking. One thing is certain: the world of independent watchmaking will continue to grow and surprise us, either from a design standpoint or through new ways in which watchmakers can approach their traditional craft.

We would like to thank Roger W. Smith, Benoît Mintiens, and Max Büsser for sharing their insight into the futuristic and future world of watchmaking.